“I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.” ~Thomas Edison

I wish I could say, after all the folding, stitching, and dyeing of the lobster piece this past week, that I was completely blown away by the success of my results once all the resist stitches were painstakingly picked out. But sadly, that isn’t the way it turned out.

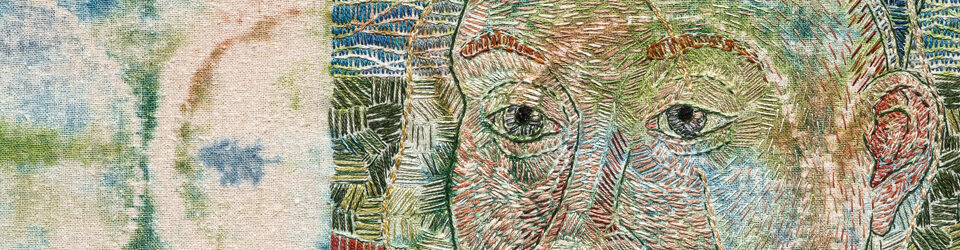

Come out, come out, wherever you are

While I’m very happy with the shibori pattern that developed, and I’m grateful for figuring out how to seat the image within that pattern, it’s a huge disappointment that the embroidered lobster image has become completely lost and is now practically invisible. It’s a ghost lobster, if you will. Somehow I have to puzzle out how to illustrate the idea of ‘hidden in plain sight’, but it will have to include the one thing that is sorely missing, the root of my misstep: contrast.

I’m headed back to the drawing board.

Ghost Lobster

In the very beginning of my shibori journey, I came up against a similar brick wall. Some of you may have heard me tell about the first piece from my Dog Walk series – where I used stitched-resist to define the silhouette shadow. I undid those resist stitches with the same level of anticipation, only to be sorely deflated at the unremarkable results.

Shadow Walk ©2012 Elizabeth Fram, 36 x 42 inches, Stitched-resist dye, paint, and embroidery on silk

But after letting the piece simmer for a bit, I hit on the idea to break up the space with a grid of color by layering textile paint on top of the shibori image. This was followed by defining both the grid and the image with stitch. It not only solved my immediate problem, but also started me down this path I’ve been happily following for the past several years: combining shibori patterns with embroidered images.

Shadow Walk, detail ©2012 Elizabeth Fram

So, I haven’t lost heart; I’ll figure something out. Challenges are a good thing – and in the meantime the process will give me something to write about in the weeks to come.

❖

The most interesting thing I learned about this week was the work of Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717). Entomologist, botanical artist, and naturalist, she was the first person to record metamorphosis, documenting and illustrating the life cycles of 186 insect species throughout her life. Her classification of butterflies and moths is apparently still in use today.

Check out the link above to get an idea of the height of her mastery.

Illuminated Copper-engraving from Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium, Plate VI. 1705 by Maria Sibylla Merian

She created volumes of spectacular botanical illustrations. They were painted in watercolor because, as a woman, the guilds of her time wouldn’t allow her to use oil paints. In 1699, at the age of 52, she traveled to the Dutch colony of Surinam so she could sketch the animals, plants, and insects there. Her journey was remarkable for the fact that she was able to undertake it in the first place, and all the more so because it was sponsored by the city of Amsterdam.

Plate 1 from Metamorphosis in Surinam by Maria Sibylla Merian

Everything else aside, with the heat we’ve experienced this week, can you imagine traveling to and working in the tropics dressed in the many long layers of dress worn by women in 17th century?

And on another note, I wonder if Merian’s work was inspiration for Mary Delany? It must have been.

Another informative post! I loved learning about Maria. Thank you Elizabeth!

Wasn’t she amazing? Glad you enjoyed reading about her.